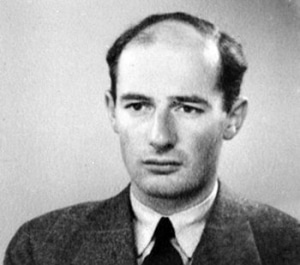

“For Me There’s No Choice”: The Life of Raoul Wallenberg

Wallenberg was born in 1912 to a prominent and successful family in Sweden, a privilege that allowed him to study architecture abroad at the University of Michigan. While there, he studied hard, finished early, and graduated-along with future President Gerald Ford-at the top of his class. The market for architects in Sweden was small, however, so after graduating he moved first to Cape Town, South Africa, and then to Haifa, in what was then Palestine (now Israel), to take a job in a Dutch bank office. It was there, in Haifa, that Wallenberg first met Jewish people who had escaped the Nazi persecution that was beginning to take root in Germany. Their stories affected him deeply.

Shortly after his return to Sweden in 1936, Wallenberg went into business with a Hungarian Jew named Koloman Lauer, owner of the Mid-European Trading Company. Lauer needed Wallenberg because, as a multi-lingual Swede (Sweden remained neutral throughout World War II), he was able to conduct business in Germany, occupied France, and other regions that were becoming increasingly closed and cautious due to the international political scene.

Stopping the “Final Solution”

It was during the spring of 1944, when Wallenberg would have been in his early 30s, that the world first truly came to grips with the reality of Hitler’s “Final Solution.” It was also in the spring of 1944 that the German army invaded Hungary, which was still home to an estimated 700,000 Jews. As the Allied forces heard undeniable, horrific stories of the genocide that had been taking place in Europe for years, Hitler began deporting Hungarian Jews to the death camps.

The Jewish population of Budapest knew their time of relative safety was at an end, and began to seek help from the neutral countries whose embassies remained in the city. The Swedish embassy negotiated with the Nazis that persons with special Swedish protective passes would be treated as Swedish citizens and therefore exempt from wearing the telltale yellow Star of David on their chests. Per Anger, the Swede who contrived this plan, is among the persons honored by the nation of Israel as a righteous Gentile.

The Swedish embassy quickly dispensed 700 passes, but realized that this number was inconsequential in comparison to the population of Jews still remaining to be saved. The Swedish legation also received help from the Red Cross, headed by Valdemar Langlet, who rented a number of buildings that were renamed such things as “The Swedish Library” or “The Swedish Research Institute.” These structures were then used as hiding places for Jews, a practice that caught on among other neutral embassies in the city. With so much to be done, the Swedish diplomats sent a request for reinforcements to Stockholm.

The timing of the Swedish effort corresponded nicely with the creation, in the United States, of the War Refugee Board (WRB), a government organization created to save Jewish people from Nazi persecution. The WRB learned of Sweden’s activity in Budapest, and moved to launch a joint effort to rescue the Jewish population of Budapest, as it was the last Jewish community relatively untouched by the Nazi juggernaut. The ultimate choice to lead this mission was Raoul Wallenberg.

Timing is Everything

Wallenberg was ready to begin as early as June 1944, but not without some stipulations. Given his extensive experience doing business both in Sweden and in occupied Europe, he knew what bureaucracies existed and how to move around them. He demanded total control of the project, including authorization to deal with whomever he chose, in whatever manner he chose. He used everything from bribery to the threat of blackmail to outright lying in an effort to save Jewish people from certain death–and it worked.

Wallenberg arrived in Budapest in July, 1944, when only about 230,000 Jewish people remained in the city. From the once thriving Jewish community, 400,000 people had already been deported, presumably to extermination camps, between May 14 and July 8. What’s more, there is evidence that Adolf Eichmann, Hitler’s SS officer in charge of the “Jewish question,” had created a plan to decimate the remaining Jewish population within a matter of days.

Remarkably, a letter from the King of Sweden, Gustav V, seems to have halted Eichmann’s plan in its tracks. In it, the King implored the Hungarian head of state, Miklós Horthy, to stop the deportations. Horthy promised to do “everything in his power to ensure that the principles of humanity and justice would be respected.” The deportations were called off, and a train that contained 1,600 Jewish people was stopped at the border and returned to Budapest.

“Bluffing” His Way Through

Wallenberg’s primary duty upon arrival in Budapest was to create a protective pass for the local Jews. Knowing that documents which appeared to carry some weight–an appearance he generated with colorful crests, stamps, and signatures–would pass unquestioned by officials both German and Hungarian, Wallenberg created a pass that worked exactly as he hoped, despite the fact that it carried no actual significance in local or international law. Wallenberg had permission to issue 1,500 of these passes. After multiple rounds of negotiations, he managed to raise this quota to 4,500. In reality, though, he issued almost 15,000 protective passes, utilizing a staff of several hundred, all of whom were Jewish people given safety through their Swedish employers.

In October, the national situation in Hungary took a turn for the worse. The Germans seized control of the government, deposed Horthy, and replaced him with the leader of the Hungarian Nazi party. The new government attempted to undo the legality of the Swedish protective passes, but Wallenberg began working behind the scenes among influential friends, and this drastic decision was avoided.

At this time, Wallenberg added a new dimension to his rescue program: He began safe houses. He acquired 30 houses in the city, hung the Swedish flag from them, declaring them Swedish territory, and allowed Jews to seek refuge there. The population of the Swedish houses soon reached 15,000.

One of Wallenberg’s coworkers in Budapest, future Congressman Tom Lantos, said of the Swedish diplomat, “He bluffed his way through. His only authority was his own courage. Any officer could have shot him to death. But he feared nothing for himself and committed himself totally.”

The Beginning of the End

The situation in Hungary became desperate. Eichmann began his “death marches,” ordering thousands of Jewish people to leave Hungary by foot. But Wallenberg was himself present for these deportations, handing out a simplified form of the protective pass to people as they marched away, distributing food and medicine as he was able. Eichmann continued to deport Jews to death camps via train as well, but Wallenberg went to the depots, crawling onto trains as they waited to depart and forcing passes inside to the prisoners. German soldiers were given orders to open fire if they saw him, but they deliberately missed, impressed by his courage as he ran along the roofs of the cars, thrusting bunches of passes down to the people inside. Even these simplified, hastily distributed passes continued to prove effective for those who had them.

Wallenberg apparently met Eichmann on more than one occasion. Toward the end of the war, he asked the prominent Nazi, “Face it. You’ve lost the war. Why not give it up now?” Eichmann reportedly threatened, after explaining that he considered the extermination of Hungary’s Jewish population to be unfinished business, “Don’t think you’re immune just because you’re a diplomat and a neutral!” But Wallenberg seems to have been unaffected by such ominous statements.

A friend once encouraged Wallenberg to be more concerned about his personal safety. Wallenberg reportedly replied, “For me there’s no choice. I’ve taken on this assignment and I’d never be able to go back to Stockholm without knowing inside myself I’d done all a man could do to save as many Jews as possible.”

As the situation worsened, Wallenberg intensified his efforts. He moved nearer to the Jewish ghettos, and began seeking Nazi officials to bribe. He discovered a plot to massacre the residents of the larger of the two ghettos, and sent a personal note to the general in charge of the planned attack. In it, he explained that, after the war, he would personally ensure that the general would be hanged as a war criminal. The massacre never happened, and the general himself credited Wallenberg with saving 70,000 lives through that action alone.

Two days later, the Russians entered the city and found 120,000 Jews living there, including 97,000 in the two ghettos.

A Legacy of Self-Sacrifice

Sadly, the fate of Raoul Wallenberg after the war remains unclear. What is known is that, when the Russians entered the city in January 1945, Wallenberg requested to visit the Soviet military headquarters in the city and was given permission to do so. He was never seen again. The Soviet government claimed for many years that he died of a heart attack as a prisoner on July 17, 1947, but no documentation exists today to validate that claim.

Theories as to Wallenberg’s fate abound. Some suggest that, knowing of Russian antisemitism, he wanted to visit the Russians to explain his plan for the postwar support of surviving Jewish people. Others say that the Soviets suspected him of acting as an American spy, and arrested him accordingly. Still others suggest that he survived in the 1950s or 70s. At the time of the disappearance, a rumor circulated that he was killed before he ever arrived at the Soviet headquarters, though witnesses say that he did make it to Moscow and, ultimately, a prison cell. Sweden did not take a strong approach to the Wallenberg case until the mid-1950s.

Fortunately, Wallenberg’s name and legacy have been reclaimed from obscurity. A man of such remarkable courage, such chutzpa in the face of unspeakable evil, deserves to be remembered not only by those whose relatives survived the Budapest ghetto of 1945, but by all those who consider themselves friends of God’s chosen people.