Some link Christian Zionism with dispensational theology. Still, it is crucial to recognize Christian Zionism is not just biblical. It is deeply rooted in historical Christian theology. Even many of the church fathers who held to supersessionism (the belief the church replaced Israel) anticipated Jewish people’s future restoration to the land of Israel. In this article, we will trace the historical roots of Christian Zionism—from second-century church father Justin Martyr to twentieth-century Reformed theologian Karl Barth. This legacy highlights how influential believers across various theological persuasions have anticipated the Jewish restoration to Israel.

Photo by Jose Marroquin on Unsplash.

Christian Zionism in Early and Medieval Church History

Early church fathers like Justin Martyr (100–165 CE) envisioned the millennium (Revelation 20) in Jerusalem. He affirmed this truth despite believing the church replaced Israel in God’s plan. Irenaeus (c. 130–202 CE) foresaw the rebuilding of Jerusalem, anticipating a return of people “from all the nations” to the land, not solely the Jewish community.[1] Tertullian (160–225 CE), in contrast, believed in the restoration of Jewish people to the land of Israel. These fathers held a common belief in an earthly millennium in which Israel plays a significant role. They may not have agreed on all the details, but they affirmed a distinct future for Israel.

The trajectory of Christian views of Israel took a turn with the writings of Origen (184–254 CE). Influenced by Greek philosophy, Origen merged Greek ideas with Christian theology. This thinking led him to believe the material world was inherently evil. So, Origen and others concluded an earthly kingdom with physical blessings, including Israel’s restoration, was problematic. As Origen wrote, “An earthly kingdom of Christ with its many physical blessings would be something evil.”[2]

Sandro Botticelli, “Saint Augustine in His Study” (source: Wikimedia Commons).

Origen also interpreted prophecies allegorically. He suggested Jesus’ advent fulfilled all prophecies about the messianic age. Thus, he claimed, one must take prophecies about Israel spiritually rather than literally.[3] This symbolic interpretation diminished hope for the Jewish return to Israel in the last days.

Augustine (354–430 CE) adopted Origen’s allegorical approach. He espoused amillennialism, viewing the millennium as spiritual, not earthly. Amillennialists reject a literal reign of Jesus on earth.[4] Augustine’s views gained wide acceptance in the church, thus the medieval church largely denied the literal restoration of Jewish people to the land of Israel.

Christian Zionism in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

The Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century, spearheaded by figures like Martin Luther and John Calvin, caused significant changes in the church. However, their amillennial views aligned with Augustine’s.

Yet, among British Christians, the sixteenth century also brought renewed hope for a future Israel. In The Image of Both Churches, John Bale (1495–1563) referred to a spiritual return of Jewish people by coming to faith in Jesus. John Foxe, in his famous Book of Martyrs, described God’s promises to Israel as remaining in force. Theologian Gerald McDermott described this shift: “Once again, British readers were told there is a future for the Jewish people that is distinct from that of Gentiles and that they would play a role in God’s drama at the end.”[5]

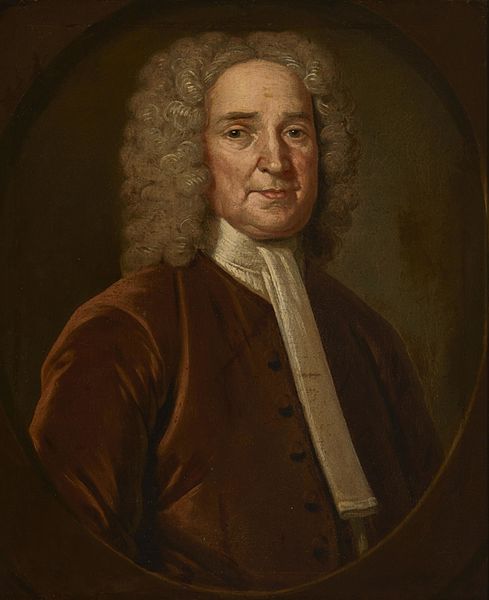

Portrait of John Cotton (source: Wikimedia Commons).

In the seventeenth century, British theologians linked Jewish belief in Jesus with a return to Israel. Puritan thinkers like Thomas Draxe, Thomas Brightman, and Patrick Forbes anticipated Jewish people would turn in faith, leading to restoration in the end times. Henry Finch, a member of Parliament and a Puritan, argued against the supersessionist reading of Scripture. He wrote, when the Bible references Israel, it means “Israel properly descended out of Iacob’s [Jacob’s] loynes.”[6]

Other notable Puritans also linked Jewish turning to Jesus with restoration in their writings. Among them were John Cotton and Increase Mather, early Massachusetts Puritans. This perspective influenced popular culture and writings of the time, echoing the permanence of Israel’s role in the end times. For instance, Andrew Marvell wrote his cavalier poem, “To His Coy Mistress” in 1681. In it, he mentioned pursuing his love until the “conversion of the Jews.”[7] In other words, until the end of time.

Christian Zionism in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries

Building on the groundwork of British and Puritan theologians, Christian thinkers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries made Christian Zionism more common and grappled with its ramifications.

Dutch Reformed theologian Wilhelmus à Brakel (1635–1711) challenged Calvin’s supersessionist theology. He instead argued the church was not the “New Israel” and acknowledged a distinct future for Jewish Israel. His writing anticipated Israel as part of the millennium, urging Gentile believers not to disregard Jewish people. À Brakel also openly spoke of a coming Jewish return to the Promised Land.

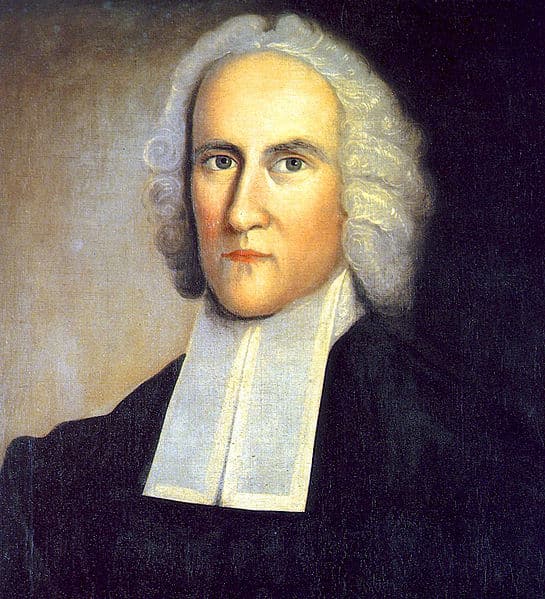

Portrait of Jonathan Edwards (source: Wikimedia Commons).

Similarly, American preacher Jonathan Edwards (1703–1758) criticized Calvin’s theology of Israel. He claimed Calvin overlooked the plain sense of Scripture. Edwards emphasized the importance of the Jewish heritage within Christianity. Further, he anticipated the Jewish return to their homeland, highlighting unfulfilled prophecies related to the land. He was convinced Jewish people would “be reconciled to their divine Parent, regain their ancient homeland, establish a polity there and regain their status as children in full favor.”[8]

British theologian James Bicheno advocated for the imminent restoration of Jewish people to the land. He was the first to urge Britain to make this restoration a goal of foreign policy. Bicheno and Edwards were both postmillennial. Like amillennialists, postmillennialists do not believe in a literal thousand-year reign of Jesus on earth. Rather, they look to Jesus’ return after the millennium.[9] They might define the millennium merely as the time before the Second Coming, or a period of peace as the gospel spreads. Lord Ashley, the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury (1801–1885), was the greatest British Christian Zionist of his century. His work helped form the basis for the Balfour Declaration.[10] This 1917 statement solidified British support for a Jewish return to the land.

Christian Zionism in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

With the advancement of political Zionism in Europe, a refined theology concerning Jewish people emerged. Figures like Russian Orthodox priest Lev Gillet (1893–1980) described Jewish people as having “priority” as “elder sons.”[11] Mother Basilea Schlink (1904–2001), who founded a Lutheran cloister in Germany, saw the founding of modern Israel as a miracle and a sign of God’s faithfulness. She considered the Jewish return to Israel as evidence God’s covenant promises remain in effect.[12]

Karl Barth (source: Wikimedia Commons/German Federal Archive).

Karl Barth, one of the most influential twentieth-century theologians, also supported Israel. He believed the modern state played a role in God’s redemptive purposes. Barth even foresaw Israel being involved in a global revival at the end of days.[13] Today, although many view Christian Zionism as a marginal position in the church, theologians from various backgrounds still see Israel’s existence as a sign the land and people of Israel still matter. For instance, Roman Catholic Gary A. Anderson supports the Jewish claim to the land of Israel based on biblical premises.[14]

Conclusion

Christian Zionism is not solely a product of dispensational or even Protestant belief. Throughout history, Christians from diverse theological backgrounds anticipated Jewish people’s restoration to the Jewish homeland. Whether Roman Catholic, Lutheran, or Russian Orthodox, many Christians have come to a similar conclusion about Israel. Regardless of one’s theological stance, supporting the State of Israel aligns with both Scripture and the rich traditions of the Christian faith.

Header photo by Akhil Lincoln on Unsplash.

[1] Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 5.34.1, www.newadvent.org/fathers/0103534.htm.

[2] Paul N. Benware, Understanding End Times Prophecy: A Comprehensive Approach, rev. and expanded ed. (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2006), 121.

[3] Gerald McDermott, “A History of Christian Zionism,” in The New Christian Zionism: Fresh Perspectives On Israel and the Land, edited by Gerald McDermott (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2016), 55.

[4] Benware, Understanding End Times Prophecy, 123.

[5] McDermott, “A History of Christian Zionism,” 58.

[6] Henry Finch, The Worlds Great Restauration, or, The Calling of the Iewes (London: Edward Griffin and William Bladen, 1861), A2–A3, 5–6.

[7] Andrew Marvell, “To His Coy Mistress,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/44688/to-his-coy-mistress.

[8] McDermott, “A History of Christian Zionism,” 65.

[9] Benware, Understanding End Times Prophecy, 141–142.

[10] McDermott, “A History of Christian Zionism,” 58.

[11] Lev Gillet, Communion in the Messiah: Studies in the Relationship Between Judaism and Christianity (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1999), 185, 161.

[12] McDermott, “A History of Christian Zionism,” 58.

[13] Ibid, 72–73.

[14] Ibid, 72.