What does France make you think of?

The Eiffel Tower? Warm croissants? Designer fashion?

France is, of course, famous for its cuisine, art, fashion, philosophy, history, and architecture. One aspect of France that is not as well-known is its large Jewish population. Indeed, France is home to the world’s third-largest Jewish community—surpassed only by Israel and the United States.[1] Chosen People Ministries has been active in France since the early 1930s. There is a great need for French Jewish people to hear about the Messiah.

The task of sharing the gospel in France, however, must overcome many obstacles. Modern-day France, like most of Europe, is a deeply secular country. Not only are most French Jewish people nonreligious themselves, but it is unlikely they will see the gospel lived out in personal relationship. Still, God is at work. Click here to hear the story of one French Jewish man who put his trust in Yeshua.

Knowing the history of a community can be an incredibly helpful step in preparing to share the gospel with them. Since Jewish people have been part of France for centuries, this article will look at five famous Jewish people who have called France home.

1. Rashi

Painting of Rashi (Source: Bible Researcher)

Rashi, short for Rabbi Shlomo Yitzhaki, is one of the most influential rabbis in Jewish history. He lived in the eleventh century in Troyes, the hub of an important trade route in northern France. Like his father, he made a living selling wine. Rashi studied with Torah scholars in Worms, Germany.

He is famous for writing commentaries on almost the entire Hebrew Bible and Talmud, a huge collection of Jewish law. His passion was to make the complex teaching of these writings accessible to more people. Rashi also wrote piyyutim, poems that accompany parts of the liturgy.

As with many key historical figures, there are legends about Rashi’s life. One story claims that he was too humble to publish his commentary openly. Instead, he wrote on small sheets of paper and left them in various yeshivas (Jewish religious schools). As the scholars found these papers, they were amazed and compiled them into a book. One day, someone saw Rashi leaving a paper and discovered his secret. The scholars then praised Rashi for his insight.[2]

His notes on the Bible highlight the plain meaning of a passage. While earlier interpreters often discussed Scripture with an eye toward application, Rashi focused more on what the text simply says. Historian Martin Goodman wrote, “What ensured that Rashi’s commentary superseded all those before it was his unique ability to clarify the methodology of the Talmud . . . bringing the text alive.”[3]

Rashi’s comments were so well-received that today they are printed in most modern copies of the Talmud. His writing also affected Christian scholars, including Nicholas of Lyre. Rashi’s sons-in-law and grandsons became well-known Jewish scholars as well.

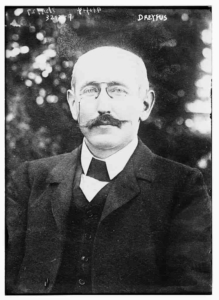

2. Alfred Dreyfus

Photo of Alfred Dreyfus (Source: Store Norske Leksikon)

What happened to Alfred Dreyfus, a secular Jewish man, was shocking. It dashed many Jewish people’s hopes of being accepted in modern Europe. For centuries, Europe had codes that limited the rights of Jewish people. Some laws, for instance, barred them from living in certain areas. Others placed strict quotas on how many could attend state schools. In the mid-1800s, western Europe began to ease these laws. Of these countries, France was perhaps most open to Jewish participation in society.

Dreyfus became an officer on the French general staff counsel. His success, however, shattered when he was framed for treason in 1894 and imprisoned in January 1895. Forged documents claimed that he had given military secrets to France’s enemy, Germany.[4] A court martial sent Dreyfus into exile on Devil’s Island, off French Guiana. The French expressed anger, not only at Dreyfus, but against all Jewish people. Many chanted “death to Jews.”

Dreyfus, who insisted he was innocent, also had some supporters. The famous writer, Émile Zola, published an open letter titled “J’accuse . . . !” Zola denounced Dreyfus’ exile and called for his release. This letter caused Zola himself to receive a one-year prison sentence, though he fled to Britain. The president eventually pardoned Dreyfus, but many still considered him guilty.

It was not until 1906, twelve years after his court martial, that he was officially vindicated. The supreme court reviewed the evidence and found him not guilty.[5] Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, was among those who saw the antisemitic riots surrounding the Dreyfus affair. This event played a role in convincing Herzl that Jewish people needed their own homeland.

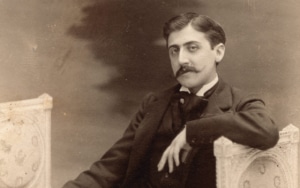

3. Marcel Proust

Photo of Marcel Proust (Source: Literary Hub)

Marcel Proust is considered one of France’s greatest literary voices of the twentieth century. He was born in 1871 in Auteuil, a suburb of Paris. His parents were both well-educated, and he had one younger brother. A doctor, his father married a woman from a wealthy Jewish family to increase his standing. Proust studied law and philosophy but knew his true calling was writing. He slept through the day and wrote at night. He even had his bedroom lined with cork to drown out the daytime noises of Paris.

Here are some of his books:

- In Search of Lost Time

- The Guermantes Way

- Sodom and Gomorrah

- The Captive

- The Fugitive

- Time Regained[6]

In Search of Lost Time, a seven-volume novel, is Proust’s most famous work. Though fictional, many scholars see it as partly autobiographical. The narrator recalls his life in upper-class French social circles. His memories, from youth to old age, form the basis of the novel. While Proust was not vocal about his Jewish heritage, one of the characters, Charles Swan, is Jewish. Like Proust and many other Jewish people of the time who were raised in a culturally Christian way, Swan feels stuck between two worlds. While he is generally accepted among the French elite, he remains aware of how quickly antisemitism can spring up.

The Dreyfus affair, which brought to light the antisemitism of many French people, occurred during Proust’s life. Unlike most of the people with whom he associated, Proust supported Dreyfus.[7] Proust died of pneumonia in 1922. Three of his books were published posthumously. His masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, never went out of print and is available in more than thirty languages.[8]

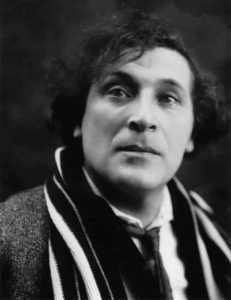

4. Marc Chagall

Photo of Marc Chagall (Source: Store Norske Leksikon)

French painter Marc Chagall was born in 1887 in Vitebsk, Russia. He attended a local art school before moving to St. Petersburg with a friend. Like many young Russian artists, he saw that there were many more opportunities in Paris than his home country. In 1911, he went to Paris and settled in La Ruche (the hive), an artist’s colony. He returned to Russia in 1915 to marry. Several years later, he came back to France and became a French citizen.

Many his works were part of the Nazi display of “degenerate” art, pieces they deemed unfit. This category included modern art, pieces with anti-Nazi themes, and pieces done by artists they considered racially inferior.[9] Many of these pieces were done by Jewish artists.

During the war, Chagall fled to New York. He returned to France in 1948 and worked on paintings and stained glass for many different settings. For instance, he designed mosaics and wall panels for the parliament building in Jerusalem. He also worked on costumes and sets for the Metropolitan Opera in New York.[10]

Chagall completed many paintings with Jewish and biblical themes. For the portrait The Praying Jew, he had someone pose in his father’s tefillin (small boxes with Scripture that Jewish men traditionally wear during prayer).[11] One of his most stirring paintings, White Crucifixion (1938), depicts Jesus in a clearly Jewish way.[12] Jesus is wearing a prayer shawl and is surrounded by Jewish people fleeing persecution. A synagogue is burned, and a man tries to save a Torah scroll. Jesus’ death is a common image in art, but Chagall’s work uniquely reveals His Jewishness. White Crucifixion also connects Jesus’ suffering with that of Jewish people in 1930s Europe.

5. Claude Lanzmann

Photo of Claude Lanzmann (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Journalist and filmmaker Claude Lanzmann is most well-known for producing Shoah (Hebrew for “catastrophe”), a nine-and-a-half-hour film compiling eyewitness accounts of the Holocaust. The oldest of three children, he was born in France to a Jewish family. During the war, Lanzmann led a Communist youth Resistance group. He studied philosophy at the University of Tübingen and taught at the Free University in Berlin. While writing for Le Monde, a French paper, he met the philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. For many years, Lanzmann edited Sartre’s journal, Les Temps Modernes.[13]

He was friends with and counseled former French president François Mitterand. His first film, Why Israel? came out in 1973. Shoah (1985) was the result of eleven years of research and 350 hours of interviews. The interviewees included both survivors of the camps and perpetrators. Lanzmann posed as pro-Nazi to gain the trust of and secretly film former SS members.

Some criticized Lanzmann for forcing people to relive the worst moments of their lives. Others complained he focused too heavily on antisemitism in post-war Poland while ignoring France’s collaboration with the Nazis.

The vast archive of footage not used in Shoah was the basis for more Holocaust films. In 2001, he released Sobibor: October 14, 1943: 4pm. This documentary tells how a group of Jewish and Russian prisoners escaped the Sobibor death camp. His later films include The Karski Report (2010), The Last of the Unjust (2013), and Napalm (2017). Lanzmann died on July 5, 2018.[14]

Conclusion

Studying the lives of these five famous Jewish people from France reveals much about Jewish history and culture.

- Rashi’s influence highlights how central the Talmud is to Judaism.

- Alfred Dreyfus’ ordeal dashed many Jewish people’s hopes of having the same rights as non-Jewish Europeans.

- Marcel Proust’s writing reflects his complex Jewish identity. This angst is common to many people who have one Jewish parent but were not raised in a Jewish way.

- Several of Marc Chagall’s paintings depict Jewish life in eastern Europe before the Holocaust.

- Claude Lanzmann created the well-known epic documentary on the Holocaust, Shoah.

Learning about Jewish history shows that we care. If we want to get to know an individual, we should learn about their background. We might, for instance, ask about their education and where they grew up. Something similar happens when we learn about a group’s history. Understanding their past helps us understand who they are today. Being at least somewhat familiar with major themes in Jewish history can open the door for rich conversation. Our knowledge of history can help build bridges to talk about the greatest Jewish person of all time, Jesus.

Notes

[1] “France,” World Jewish Congress, accessed January 18, 2022, https://www.worldjewishcongress.org/en/about/communities/FR.

[2] Rabbi Eli Brackman, “Rashi,” Oxford Chabad Society, accessed January 18, 2022, https://www.oxfordchabad.org/templates/articlecco_cdo/aid/329653/jewish/RASHI-Biography.htm.

[3] Martin Goodman, A History of Judaism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018), 319.

[4] Goodman, A History of Judaism, 443.

[5] Alan Riding, “Dreyfus Was Vindicated, but What of the French?” New York Times, July 7, 2004, accessed January 19, 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/07/world/europe/07dreyfus.html.

[6] William C. Carter and Nicolas Drogoul, “Marcel Proust: Biography,” Proust Ink, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.proust-ink.com/biography.

[7] Lena Shilony, “Proust: Jew, Jewish-hater or Both?” Haaretz, December 27, 2013, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.haaretz.com/.premium-proust-jew-or-jewish-hater-1.5304337.

[8] William C. Carter and Nicolas Drogoul, “Marcel Proust: Chronology,” Proust Ink, accessed January 20, 2022, https://www.proust-ink.com/chronology.

[9] “Degenerate Art,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed February 11, 2022, https://www.britannica.com/art/degenerate-art.

[10] Ingo F. Walther and Rainer Metzger, Chagall (Cologne: Taschen, 2020), 7–10, 93–95.

[11] Marc Chagall, The Praying Jew, 1923, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, accessed January 21, 2022, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/23700/the-praying-jew.

[12] Marc Chagall, White Crucifixion, 1938, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, accessed January 21, 2022, https://www.artic.edu/artworks/59426/white-crucifixion.

[13] Julia Pascal, “Claude Lanzmann Obituary,” The Guardian, July 5, 2018, sec. Film, accessed February 14, 2022, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/jul/05/claude-lanzmann-obituary.

[14] Pascal, “Claude Lanzmann Obituary.”